The New Face of Small Business: The Role of the Latino Entrepreneur in the Revitalization of the US Economy

Scott Astrada & Carolina Rizzo

Introduction

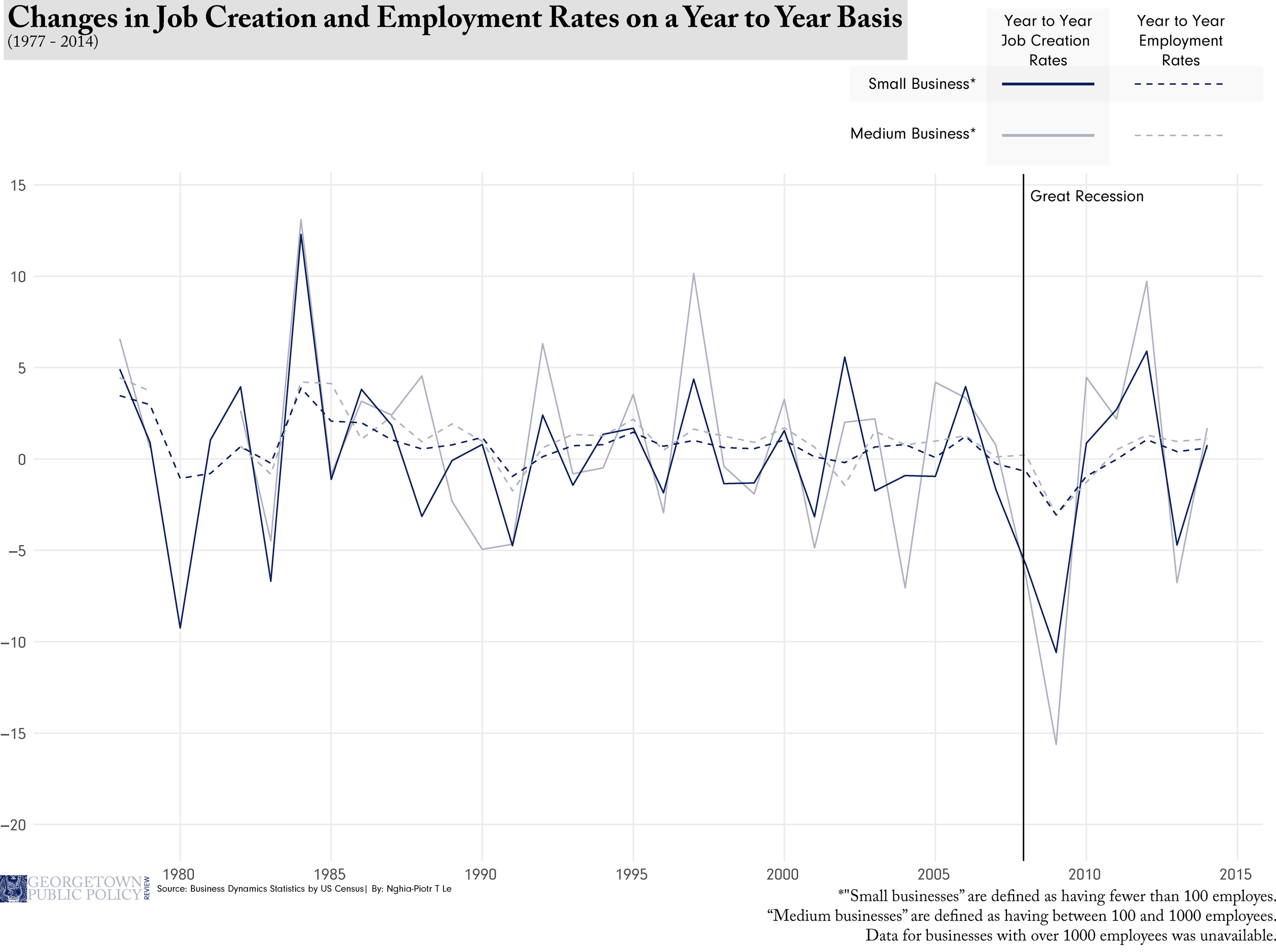

The United States has long been home to one of the most entrepreneurial, innovative and flexible economies in the world. This dynamism has driven economic growth and allowed the US economy to adapt to changing circumstances and recover relatively swiftly from the worst of the recent economic recession.[i] However, the Great Recession of 2008 had a devastating and lasting effect on all aspects of the economy, from the largest global financial institutions to Main Street America.[ii] Notably, the Recession culminated a decades long trend of decreased small business growth and left in its wake a sharp downturn in job creation.

This trend of decreased growth is of central importance, because in the U.S., small businesses are the chief drivers of job growth, innovation and economic adaptability, and they are responsible for the majority of new job creation.[iii] Since the early 2000s, small business growth and labor market fluidity have been steadily declining.[iv] The 2008 recession saw the lowest overall rate of gross job creation and job creation from startups since 1980.[v] Furthermore, business creation has experienced its steepest decline since the early 1990s.[vi] The decline of business startup rates and the resulting diminished role of new businesses in the creation of employment and economic opportunity are warning signs calling for strategic policy-making. And Latino Entrepenerus are readily positioned as a viable policy solution.

“Latinos are not only the fastest-growing minority in the US, they are also starting businesses fifty times faster than any other demographic group.”

Latinos are not only the fastest-growing minority in the US, they are also starting businesses fifty times faster than any other demographic group[1] , making them key actors in reigniting economic growth and small business job creation.[vii] However, there are a variety of unique challenges facing Latino business owners, such as restricted access to capital and difficulty breaking into high growth industries. In addition, despite this noteworthy trend of growth, Latino businesses remain relatively small. The over 3 million Latino-owned businesses have an average of only 8.6 employees.[viii] This is concerning given that, from 2007 to 2012, about 60 per cent of job loss in the US occurred at businesses with fewer than 50 employees.

Defining the underlying factors of these economic trends has proven to be a challenge both in academia and amongst policy makers. Even more apparent is the lack of prioritization of policy solutions that are aimed at empowering Latino entrepreneurs. In fact, fostering the explosive growth of Latino entrepreneurship has largely been left out of these analyses as a potential policy solution altogether. This omission is serious because harnessing the economic potential of Latino entrepreneurs could provide a major solution to both the trend of declining small business growth as well as sustainable job creation.

In this paper, we examine the particular role Latino entrepreneurs play in the context of policy solutions available to Congress to spur economic growth and support the job creating function of small businesses. Furthermore, we find that there is substantial reasoning for Congress to act in support of Latino small businesses as a means of driving community economic development.[ix]

The Decline of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Creation in the United States

In the current economic recovery, the growth of young and small businesses has been especially slow, with many of these businesses still reeling from the Great Recession.[x] Small businesses already struggle to succeed due to their extremely high failure rates in the first 10 years of operation.[xi] Surviving young businesses, however, have contributed significantly more to the US economy than larger and more established businesses in terms of job creation.[xii] On average, between 1980 and 2010, 16 million jobs were created annually in the United States.[xiii] Of these jobs, almost 6 million were created by new businesses or new establishments of existing firms,[xiv] and 2.9 million jobs (of the 6 million) were created solely by new firms.[xv]

“High labor market fluidity—which refers to the rate at with which workers move between jobs—drives productivity gains, earnings growth, and job creation.”

In addition to the decrease in the number of young and small businesses, policy makers should also be concerned about the decline of labor market fluidity. High labor market fluidity—which refers to the rate at with which workers move between jobs—drives productivity gains, earnings growth, and job creation.[2] [xvi] Historically, the movement of workers across multiple jobs and industries has directed the shift of human and economic capital from less productive businesses to new and more productive businesses, capitalizing on either new technologies and innovation or new services.[xvii] Labor market fluidity also correlates with high employment rates, more job openings, and shorter unemployment spells.[xviii] Startups and high growth young firms are central to these processes since, in addition to providing employment opportunities, they are often laboratories for innovation and experimentation.[xix]

The decline in entrepreneurship, labor market fluidity, and business dynamism have only been partially explained by research.[xx] Haltinwanger notes that the decline in business dynamism has accelerated after 2000 and is affecting different industries and businesses than in previous years.[xxi] Multiple factors are contributing to this less fluid labor market, including an aging workforce, a shift away from younger and smaller employers, transformation in business models, changes in hiring practices and restrictions on occupational labor supply.[xxii] This seems counterintuitive in a constantly digital and interconnected world, but ultimately today’s workers are less likely to secure employment after being unemployed, switching jobs, or taking jobs across state lines.[xxiii]

Latino Entrepreneurs in the US Economy Today

Due to their demographic and entrepreneurial growth, and the rate at which they are opening businesses, Latinos are becoming the new face of American small business. Besides opening businesses at a faster rate than any other group in the country, Latinos represent a substantial consumer base and the fastest growing portion of the workforce.[xxiv] In 2010, Latinos made up roughly 16 percent of the US population; by 2050, this is expected to double to 30 percent. In fact, in 2015, the Latino population had $1.3 trillion of buying power - more than the GDP of Spain.[xxv] Additionally, Latino entrepreneurship creates a positive feedback loop by generating economic empowerment and opportunity for other aspiring Latino entrepreneurs, creating incredible potential for further growth.

In contrast to the general decline of small business dynamism and job growth, the number of new Latino-owned businesses has exploded in recent years.[xxvi] Latino entrepreneurs have been opening businesses and driving economic progress at a rate three times faster than the national average, outpacing all other ethnic groups, even when considering the varying rates of underlying population growth.[xxvii] Specifically, the number of Latino-owned businesses grew 46 percent from 2007 to 2012, compared with a decline of more than 2 percent for non-Latino businesses.[xxviii] The economic contributions of Latinos are significant and increasing: in 2013 alone, 3.1 million Latino small businesses contributed a projected $468 billion to the American economy.[xxix] A closer look at the growth in the number of small businesses between 2007 and 2012 shows that 86 percent of the growth in all small businesses during this time can be attributed to Latino owned businesses. In fact, without Latino owned businesses there would be a significant drop in the overall number of small businesses created.[xxx]

“As the fastest growing subset of overall Latino entrepreneurship, Latinas represent the future success of (overall) Latino entrepreneurship. ”

The accelerated growth of Latino entrepreneurship is observed most strongly among females, with the National Women’s Business Council reporting an increase of 172 percent in their businesses between 2002 and 2007.[xxxi] In the last five years, the Latina business ownership rate has been six times the national average.[xxxii] As the fastest growing subset of overall Latino entrepreneurship, Latinas represent the future success of (overall) Latino entrepreneurship. [3] Therefore, the success and growth of Latina small business should play an essential role in the revitalization of business innovation and job creation.[xxxiii]

Challenges for the Latino small business owner

Even though the number of Latino-owned small businesses is projected to exceed four million and contribute $661 billion dollars to the economy in 2016, their average number of employees and annual revenue lag behind that of non-Latino small businesses.[xxxiv] Additionally, Latino small businesses suffer from an increased failure rate compared to non-Latino owned businesses.[xxxv] While Latino entrepreneurs are starting businesses faster than any other demographic, their sales were generally flat from 1997 through 2012 (compared to a 34 percent increase from their counterparts).[xxxvi] This is coupled with data showing that less than two percent ofbusinesses owned by Latinos generate revenues of over $1 million (compared to 4.9 percent from other businesses).[xxxvii] If the sales of Latino-owned small businesses had matched the U.S. average for non-Latino businesses in 2012, they would have contributed almost $1.4 trillion, or 8.5 percent, to gross domestic product.[xxxviii] The current challenge, then, is closing the opportunity gap between Latino-owned businesses and their counterparts in terms of revenue growth and scalability.

“Relative to white-owned businesses, minority-owned businesses are subjected to higher borrowing costs, experience higher rejection rates in loan applications, and receive smaller loans.”

One of the main challenges faced by Latino entrepreneurs is the lack of access to capital—a primary predictor of business longevity and success.[xxxix] As of 2016, only 6 percent of Latino owned businesses utilized commercial loans, and less than 1 percent have had access to venture capital.[xl] Access to capital is more essential for minority business owners than for their white counterparts, since minority businesses depend disproportionately on financial institutions for capital over all other borrowing sources combined.[xli] Relative to white-owned businesses, minority-owned businesses are subjected to higher borrowing costs, experience higher rejection rates in loan applications, and receive smaller loans[4] .[xlii] These trends disproportionately impact Latino and Black entrepreneurs specifically who have less access to bank credit than their white entrepreneurs with identical credit and firm profiles.[xliii] Geography also plays a key role: minority businesses operating in minority neighborhoods tend to perform less well than those operating in predominantly white neighborhoods. Without bank loans, minority businesses rely predominantly on consumer credit that provides smaller amounts of capital at higher interest rates.[xliv] The result of these trends is that Latinos attempting to start a business are more likely to experience business failure than their white counterparts.[xlv]

The 2008 housing crisis made it even more difficult for Latinos—who on average invested a larger portion of their wealth into their homes than White homeowners—to access capital.[xlvi] A low-cost alternative to financing businesses, home equity still remains one of the most popular sources of startup capital and there is a strong correlation between home-ownership and business ownership.[xlvii] Thus, the foreclosures resulting from the financial crisis rendered aspiring Latino business owners, already struggling with lower startup funds and higher rates of loan denials, devoid of funding options.[xlviii]

Generally excluded from traditional relationships with financial institutions, and lacking business financial education, many Latino entrepreneurs instead rely heavily on informal sources of financing.[xlix] Relying disproportionately on owner equity investments and savings, and using relatively less debt from traditional sources, the average minority-owned firm operates with substantially less capital than their non-minority counterparts.[l] Further, Latino entrepreneurs tend to lack leadership and management training relative to white entrepreneurs,. In fact, some of the top barriers that many Latino business owners encounter are lack of opportunities for management and leadership skills development.[li]

Another significant obstacle for Latino entrepreneurs is there statistical likelihood of lower business profitability than other minorities and white entrepreneurs. This is a result of various factors, including their smaller than average size. Most of these businesses, defined as “microenterprises,”[lii] are not positioned to generate substantial revenue.[liii] Additionally, a significant portion of Latino businesses do not normally operate in the most profitable or fastest growing sectors of the economy.[liv] Rather, they focus mainly on the service and manufacturing industries, and lack significant representation in the innovative science and technology sectors.[lv] As a result, Latino owned businesses yield a relatively low average gross receipt per firm.[lvi] However, the sheer number of new firms that Latinos are creating offsets the low per-business sales amount. However, in additional to these factors, there are significant challenges faced by Latino entrepreneurs that are readily remediated by policy (i.e. lack of access to capital and supportive tax policy).

This is where closing the opportunity gap between Latino and non-Latino businesses is of central concern. Analyses have shown that closing the opportunity gap[lvii] for Latino-owned businesses would result in a contribution of more than $1.4 trillion a year to the U.S. economy (~8 percent of total GDP).[lviii] While recent research has pointed to additional factors that have prevented Latino Business growth outside of traditional factors such as small business size and lack of diversity of clientele, addressing the lack of access to capital could help Latino entrepreneurs overcome these other obstacles and concerns about losing equity in capital raising.[lix]

“If Latino entrepreneurs are able to thrive, the US economy is more likely to thrive as well. ”

Policies that eliminate obstacles for Latino and other minority small businesses benefit all Americans. If Latino entrepreneurs are able to thrive, the US economy is more likely to thrive as well. [5] The long-term benefits of policies that ensure the economic health of small businesses are substantial not only for business owners, but also for their employees, customers, and communities they serve.[lx] When minority businesses do well, they create jobs in communities already suffering from unemployment and underemployment.[lxi]

Policy Recommendations

Latino entrepreneurs occupy a central place in the future of the US economic recovery. Representing the fastest growing demographic of business owners, Latino entrepreneurs must have access to resources and be supported by policies that foster their enterprise and business success. Congress has a unique opportunity to improve and preserve Latino entrepreneurship, and in doing so, bolster the recovery of the overall US economy by closing the opportunity gap. The following actions will help policymakers achieve this goal:

1) Remove known barriers for Latino entrepreneurs

In answering the call to support Latino small businesses, Congress must remove known barriers to Latino entrepreneurial success. Capital access remains the most crucial of these barriers.[lxii] Providing Latino entrepreneurs with greater access to affordable loans from financial institutions would lower barriers to creation and expansion of Latino owned businesses, enable Latino business owners to strengthen their balance sheets, improve their credit ratings, and decrease their reliance on expensive forms of consumer credit. It would also provide a feasible means for Latino business owners with cash flow shortfalls to pay their bills on time. This would keep more Latino businesses open and allow firms to capitalize on opportunities to grow and compete for better clients.[lxiii]

2) Invest in highly-skilled, STEM immigration and education

As a growing amount of Latinos enter the STEM field,[lxiv] Congress should encourage education and training and remove barriers to highly-skilled, STEM-focused immigration, so that the US labor market can grow in areas that yield the most innovation and dynamism. In fact, legislation has already been introduced that that could make substantial positive impacts for Latino entrepreneurs. If enacted, the High-Skilled Immigrants Act of 2015 will eliminate country-based restrictions on employment visas.[lxv] While the Immigration and Nationality Act currently limits the combined total of work and family based visas from any country at 7 percent of that country’s population, this bill would increase that amount to 15 percent, and make that limit apply only to family-based visas and not to work-based visas.[lxvi]

Additionally, Congress should enact the Startup Act (S.181),[lxvii] introduced by Senator Jerry Moran and now awaiting a markup by the Senate Committee on Finance.[lxviii] This legislation proposes to create a conditional permanent resident status for immigrants with an advanced degree in STEM. This bill also proposes granting up to 75,000 annual immigrant visas to “qualified alien entrepreneurs.”[lxix] These are immigrants who are already lawfully present in the United States pursuant to a student or work visa, and who, within the year after they obtain this visa, start a business, employing at least two full-time employees who are not their relatives, and raising or investing at least $100,000.[lxx]

Given that Latinos are overrepresented in industries such as manufacturing, which lost the most jobs in the aftermath of the recession,[lxxi] Congress should also enact the Manufacturing Universities Act of 2015.[lxxii] This bill designates up to 25 higher education institutions as “US Manufacturing Universities” and as federal grant recipients. Institutions qualifying under this program will receive $5 million per year for four years to improve and expand engineering and manufacturing education and increase funding for research and development in the manufacturing industry. The goal is to produce a greater number of graduates starting manufacturing businesses.[lxxiii] Supporting this bill would also provide additional training and educational opportunities to Latinos, who lost their jobs in the recession, but have significant work experience in the manufacturing industry.

3) Increase support for start-up businesses

Congress should facilitate easy access to crowdfunding for the growing number of small businesses turning to public fundraising. Rep. Patrick McHenry’s (R-NC) Fix Crowdfunding Act (H.R. 4855) addresses this very challenge. The Fix Crowdfunding Act would permit small firms to crowdfund up to $5 million for their businesses without costly registrations and compliance costs with the SEC.[lxxiv] The costs of filing, and the accompanying attorney’s fees can easily put capital raising outside the capability of many small firms. The bill was passed by the House Financial Services Committee with bipartisan support, and was ultimately passed on the House floor in July of 2016. It is currently still pending in the Senate. As more Latino owned businesses are turning to e-commerce and expanding into innovative funding models, enacting this bill would empower Latino small businesses to have access to much needed capital.

4) Increase support for Small Businesses

An example of Latino business growth is from 2013-2104, when the share of new businesses started by Latinos increased from 20.4 percent in 2013 to 22.1 percent in 2014 (this is double the growth rate compared to 1996).[lxxv] To further support this growth, Congress could adopt a variety approaches that involve expanding resources available to Latino business owners. One such approach is increasing access to alternative lenders like Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) through Congressional appropriations for CDFI federal programs that are similar or above 2016 levels.[lxxvi] Finally, Congress should promote Microenterprise Assistance Pilot Projects at the state level that empower Latino small businesses, provide support, promote understanding of business laws and regulations, and are culturally appropriate and accessible to Latino and other minority aspiring entrepreneurs.[lxxvii]

Furthermore, Congress should also continue to fund the Small Business Administration (SBA), an agency that has fulfilled a critical role in providing funding and loan guarantees to small businesses.[lxxviii] Several SBA programs, such as the Historically Underutilized Business Zones (HUBZone),[lxxix] Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR), and State Trade and Export Promotion (STEP) have successfully empowered small businesses.

“Minority-owned businesses have thrived in exporting their goods on a global scale and are twice as likely to export than non-minority businesses.”

Authorized by statute to create jobs in urban and rural communities and revitalize the economy, the HUBZone Program provides federal contracting preferences to small businesses.[lxxx] In FY2014, the federal government awarded 74,812 contracts valued at $6.67 billion to HUBZone-certified businesses (with a share of these minority-owned businesses).[lxxxi] Latinos would benefit from the continuous funding of this program as the Latino population continues to expand. By granting competitive awards, the SBIR program encourages small businesses to explore and develop technological innovations, and to profit from these improvements, providing essential resources for Latino businesses that may not have access to these resources otherwise.[lxxxii] Finally, STEP awards competitive grants to states and territories to help small businesses sell their products and services abroad. Minority-owned businesses have thrived in exporting their goods on a global scale and are twice as likely to export than non-minority businesses[6] .[lxxxiii] Because of this program, small businesses in the U.S. have reached almost 100 countries resulting in over $1.1 billion in export sales. These programs must be fully funded and continuously prioritized by Congressional appropriations to ensure these critical resources continue to be available.

Conclusion

Latinos are central to revitalizing the US economy. The rapidly growing pace of Latino entrepreneurship and small businesses are the key loci for maintaining the innovation, dynamism and job creation that small businesses have historically driven. The face of the American entrepreneur is becoming more and more Latino, and the success of Latino entrepreneurship, given its rapidly growing size and economic contribution, will very much determine the success and growth of the US labor force and economy. Therefore, it is essential for Congress to address the barriers that Latino entrepreneurs face. These barriers are rooted in the historical exclusion of Latinos from the mainstream financial markets due to immigration status, educational and technical training, and non-traditional credit profiles. By acting now, Congress can bolster business growth and ensure access to resources that will drive Latino entrepreneurship success, and consequently, the overall health of the American economy.