Disasters, systems, and human rights: Reflections on a coronial inquiry

William Maley

Abstract: A single death can be a tragedy, but it can also be a disaster, in the sense that disasters reflect a form of systems failure. To demonstrate how this can be the case, this essay draws on a Coroner's report on the death of a 24-year old Iranian asylum seeker, Hamid Khazaei, taken ill at an Australian-funded offshore detention centre in Papua New Guinea. There is a paradox at the heart of this episode. The policy of offshore detention in remote locations was officially adopted to deter asylum seekers from approaching Australia on dangerously-fragile boats in search of protection. Yet while the system failed to protect the human rights of Hamid Khazaei, arguably it did so because it succeeded in keeping him out of mainland Australia, in accordance with the “humane” policy objectives of the Australian government, until he was too ill to survive. Systems grounded in the threat to do harm are likely to result in harm.

Keywords: Refugees, disaster, human rights, Australia

I. Introduction

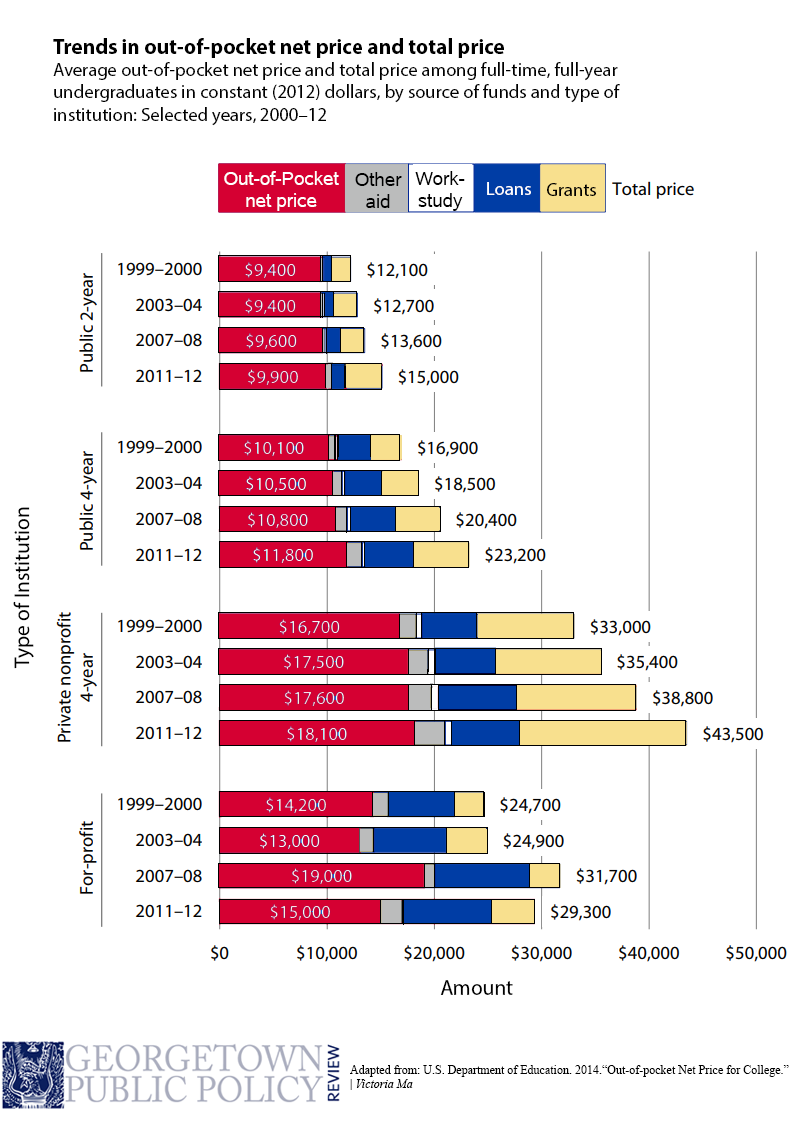

On September 5, 2014, a 24-year-old asylum seeker from Iran, Hamid Khazaei, was declared dead at the Mater Hospital in the Australian city of Brisbane. Just over a year earlier, on August 7, 2013, he had been a passenger on a boat supplied by people smugglers that entered the Australian “migration zone” near the Indian Ocean territory of Christmas Island. On September 6, 2013, he was transferred to Papua New Guinea under a “Regional Resettlement Arrangement” between Australia and Papua New Guinea that had been signed on July 19, 2013; and he was lodged at a “Regional Processing Centre” (MIRPC) on Manus Island. Although it was later held by the Supreme Court of Justice of Papua New Guinea that the detention regime was unconstitutional, Mr. Khazaei was obliged to remain in the centre (Namah v. Pato, 2016). On August 23, 2014, he sought medical attention for flu-like symptoms and a lesion on his leg, and the deterioration of his condition resulted in his being evacuated first to Port Moresby and then to Brisbane. An autopsy report subsequently found the cause of his death to be “1(a). Hypoxic-Ischaemic Encephalo-pathy, due to or as a consequence of; 1(b). Cardio-respiratory Arrest, due to or as a consequence of; 1(c). Severe Sepsis, due to or as a consequence of; 1(d). Left Lower Leg infection with Chromobacterium violaceum.”[1]

Hamid Khazaei

Image from the Refugee Action Coalition via Human Rights Law Center

Confronted with this narrative, one might well be tempted to conclude that the case of Hamid Khazaei simply reflects the reality of life: that everyone born alive lives and then dies. The loss of Mr. Khazaei in this sense could be seen as a tragedy for his family and friends, but nothing more. In this essay, however, I argue that such an interpretation does not sufficiently capture the complexities of this particular case, and that the death of Hamid Khazaei speaks to issues of public policy that deserve more detailed attention. The death of Hamid Khazaei was not simply a tragedy; it was also a disaster, in that he was the victim not just of misfortune but of a particular kind of systemic failure. But there is still more to the story than that. The system of remote detention of asylum seekers which served Mr. Khazaei so poorly was one that set out to deter asylum seekers from approaching a country such as Australia for protection in the first place, and there is evidence from the Khazaei case that this deterrent objective prevented his deteriorating condition from being managed on medical grounds alone. In other words, there were elements of the design of the system that contributed to its failing him. Human rights violations, this would suggest, can be as much the responsibility of those who design deterrent systems and put them in place as they are the responsibility of malevolent individual perpetrators or cogs in the machine. This essay is divided into four sections. The first explores various dimensions of the idea of disaster. The second, drawing on a coroner’s report into his death, shows how Hamid Khazaei came to be failed by a system, not simply by individuals. The third shows how the system to which he fell victim was one compromised by incompatible internal logics which led to a devaluing of his human rights. The fourth offer some brief conclusions.

II. The idea of disaster

In a recent overview of disasters, Etkin notes the view derived from the philosophy of Wittgenstein that some words perhaps “do not require a precise definition to be used successfully,” and expresses the belief that the word “disaster” fits into this category (Etkin, 2016). On the one hand, it is useful to have an understanding of the word “disaster” that enjoys some lexical resonance, matching to at least some degree the way in which the word is used in ordinary discourse. On the other hand, it is preferable to avoid entanglement in what Giovanni Sartori called “conceptual stretching” where “gains in extensional coverage tend to be matched by losses in connotative precision” (Sartori, 1970). For this reason, some clarification of how the term is used in this essay is warranted.

First, the idea of disaster is intimately related to the idea of harm, but there are some examples of harm to which the term does not seem quite appropriate. Principal amongst these are harms which are consciously inflicted as acts of “war” against either external or internal “enemies”: the term “disaster” might seem overly tame or euphemistic if applied to the Holocaust or the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These events, of course, differed in that the former was the product of blind racialist hatred, whereas the latter were undertaken in the hope of avoiding even more carnage and destruction (Roseman, 2012; Rhodes, 1986). All, however, involved a conscious and deliberate decision to inflict harm. The word disaster applies much more neatly and comfortably to events in the natural world: the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883, the Boxing Day tsunami of 2004, and the inundation of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Yet the natural world does not exhaustively define the stage on which disasters play out. Events such as the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912, and the crashes of airships such as the R101 in 1930 and the Hindenburg in 1937, are commonly dubbed disasters without any violence to the language. Indeed, the Hindenburg’s fiery end has acquired virtually iconic status as a disaster, since it was not only captured on film, but shared with a wide audience through a heartrending radio commentary by the broadcaster Herb Morrison.

Second, while disasters may often claim large numbers of victims, this is not necessarily the case. The term disaster has been regularly applied to the January 27, 1967 fire in the Apollo 1 space capsule at Cape Kennedy, as well as to the explosion after launch of the Challenger space shuttle on January 28, 1986, and the disintegration upon re-entry of the Columbia space shuttle on February 1, 2003. Three astronauts died in the Apollo 1 fire, and seven perished in each of the shuttle accidents, smaller numbers than the death tolls in many bus crashes and even some car smashes. What seems to have been decisive in framing these events as disasters was their shock value. The public had not been alerted to the real dangers associated with manned space flight, and whilst the Apollo 1 astronauts were not household names, some publicity had been generated about the presence aboard the Challenger of a schoolteacher, Christa McAuliffe, and aboard the Columbia of the first Israeli astronaut, Ilan Ramon. It is unsurprising that in his minority report attached as Appendix F of the Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident (the Rogers Commission), the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard P. Feynman concluded that “For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled” (Feynman, 2001).

Third, and most importantly, the idea of disaster is commonly associated with some kind of systems failure. “We are dealing with a system,” Jervis argues, “when (a) a set of units or elements is interconnected so that changes in some elements or their relations produce changes in other parts of the system, and (b) the entire system exhibits properties and behaviors that are different from those of the parts” (Jervis 1997). Even in the case of so-called “natural” disasters, systems failure can be highly relevant: In the face of obvious potential risk, either nothing may have been done to mitigate the danger, or such steps as had been taken may have proved manifestly inadequate. When, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, President George W. Bush praised Michael D. Brown, Administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, with the words “Brownie, you're doing a heck of a job,”[1] he invited ridicule because the performance of Brown and his agency had demonstrably been unequal to the challenges that Katrina’s destruction had posed.[2] Systems failure is likely to be even more obvious when problems are unrelated to natural systems (weather, climate, or tectonic forces) but arise from defects in technology or administration. The significance of systems is also implicit in a range of theoretical models of the stages of disaster, such as Turner’s disaster incubation model.[3] The case of Hamid Khazaei was not simply one of misjudgment by medical professionals; it represented a broader failure of the detention system that exposed him to risk in the first place and then complicated the management of a potentially life-threatening problem when it arose. It was fundamentally this systemic dimension that made the death of Hamid Khazaei not just a tragedy, but a disaster.

III. The death of Hamid Khazaei: systemic dimensions

Many deaths pass unremarked and unexamined but that was not the case with the death of Mr. Khazaei. Ironically, the explanation for this was that when he was medically evacuated to Brisbane on August 27, 2014, he was technically detained pursuant to the Migration Act 1958 until his death. As a result, as the coroner put it, an “inquest into his death was mandatory as he died in custody in Queensland” (para.11). Much of what we know about Mr. Khazaei’s treatment derives from the coroner’s comprehensive and illuminating report.

On the one hand, the coroner documented a complex chain of medical decisions relating to Mr. Khazaei’s sickness and assessed with care the quality and defensibility of the judgments made by medical personnel at different stages. The first set of issues related to the situation on Manus Island between Mr. Khazaei’s presentation with symptoms on August 23 of what proved to be a serious bacterial infection, and his transfer to the Pacific International Hospital in Port Moresby on August 26. By the afternoon of August 24, Mr. Khazaei was beginning to show signs of sepsis (para.87), and when his condition was no better by the morning of August 25, an emergency specialist in the Manus Island clinic, Dr. Leslie King, stated that “we need to evacuate him” (para.96). A commercial flight to Port Moresby was scheduled for that afternoon, and there were seats available, as well as a doctor booked to travel who could have acted as a medical escort for Mr. Khazaei; a “Recommendation for Medical Movement” was sent to the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection at 12:32 p,m. that day (para.120). However, it did not come to the attention of the relevant Assistant Secretary of the Department until he came to work at 8:30 a.m. on the morning of August 26, by which time of course Mr. Khazaei had missed the opportunity to be evacuated on the August 25 flight.

By the morning of August 26, there were signs that Mr. Khazaei was developing septic shock (paras.175-177). At 8.41 a.m., his transfer to Port Moresby was approved by the Department. By this stage, however, Dr. Stewart Condon of International SOS had formed the view that what he needed was to be transferred to Brisbane (para.183). Mr. Khazaei finally left for Port Moresby at 2.34 p.m. He was to spend just one night at the Pacific International Hospital, but the care he received was plainly lamentable. A crucial “Bag-Valve-Mask with Reservoir” was torn and useless (para.262) and an intravenous line had been inserted beside the vein, not in the vein (para.266). At 10.24 pm, Mr. Khazaei suffered a cardiac arrest. On the afternoon of 27 August, he was finally transferred to the Mater Hospital in Brisbane. By then he was showing early signs of brain death (para.268), which was confirmed on September 2 and 3 (para.271). On September 5, “supportive care measures were withdrawn and Mr. Khazaei died” (para.272).

It is clear from expert evidence, accepted by the coroner, that in some respects the treatment that Mr. Khazaei received on Manus Island could have been greatly improved, notably through intubation (para.328), and possibly through the administration of Gentamicin (paras.353-354). It was also clear that miscommunication occurred at numerous points. But the coroner did not limit his findings to purely clinical and communications matters. He squarely confronted the mindset of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. Dr. Yliana Dennett of International SOS had testified to the inquest that “We usually do not recommend transfers to Port Moresby. However, experience has shown that the department was very reluctant to bring patients to Australia, and we knew that if we – if we recommend transferring to Australia, it would not be approved.” (para.185) The coroner found that “It appeared that the medical staff were working primarily to clinical imperatives while the DIBP officers were working primarily to bureaucratic and political imperatives to keep transferees on Manus Island, or in PNG” (para.404), and that “the process put in place by the DIBP to approve medical transfers was overly bureaucratic and lacked clear written procedures” (para.409). He also reflected on issues of high policy. He noted that “The Commonwealth submitted that Mr Khazaei was at the MIRPC because the legislation enabling his transfer there enacted very significant and high-level government policy. This policy was designed to establish a “no advantage principle” whereby asylum seekers gain no benefit in choosing not to seek protection through established mechanisms” (para.470). In apparent response, however, he stated that “the fact that Mr Khazaei’s death occurred in the context of offshore processing cannot be overlooked.” (para.476). He made the further point that “the failures evident in the system (both human and systemic) that caused or contributed to Mr Khazaei’s death should not be sheeted home to a select number of medical practitioners or staff. I also agree that the failures of those staff should be recognized as the manifestation of the overall system, which was flawed and demonstrated a lack of capacity to meet Mr Khazaei’s immediate health needs” (para.533). Ultimately, he offered the damning conclusion that “Mr Khazaei’s death was preventable. Consistent with the evidence of the expert witnesses who assisted the court in this matter I am satisfied that if Mr Khazaei’s clinical deterioration was recognized and responded to in a timely way at the MIRPC clinic, and he was evacuated to Australia within 24 hours of developing severe sepsis, he would have survived” (para.14).

IV. Incompatible logics and human rights

While the jurisdiction of the coroner did not provide him with the scope to address broad political and administrative issues, a number nonetheless emerge very clearly from his analysis and findings, as well as from wider information on Australian policy towards refugees. Australia has a long history of respect for human rights. It is currently an elected member of the UN Human Rights Council, it is a party to key international instruments protecting human rights and giving effect to the aspirational ideas set out in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and domestically it benefits from the activities of a statutory body, the Australian Human Rights Commission, which on occasion has been admirably active in defending vulnerable groups, including detained asylum seekers (The Forgotten Children, 2014). Australia also historically had a good reputation for the treatment of refugees; indeed, it was Australia’s accession in 1954 to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees that led to that treaty’s coming into effect.

In recent times, however, a range of calculations have driven Australian policies in a hardline direction. The rise of the far right “One Nation” party in the late 1990s alarmed the then government, which sought to appease potential far right voters by adopting One Nation’s rhetoric and policies targeting asylum seekers approaching Australia by boat (Maley, 2014). The result was the so-called “Pacific solution,” pursuant to which such asylum seekers would be removed to states such as Nauru and Papua New Guinea. Given its political rationale, there was nothing particularly moral about the Pacific solution, and so the search began for a justification that could at least be dressed up as somehow ethical (Every, 2008). What resulted was the claim that asylum seekers had to be deterred from attempting to reach Australia by boat because of the danger that they might otherwise perish in rough seas between Indonesia and the Australian territory of Christmas Island to which boats typically headed. This claim carried unsettling overtones of superiority: that the kind of people boarding boats could not possibly understand what was really in their interests, and therefore required Australian politicians – who had typically never experienced the threat of persecution or gross human rights violations themselves – to think on their behalf.[1] There was also a considerable cynicism to the claim: In November 2009, the U.S. Embassy in Canberra sent a cable to Washington on boat arrivals reporting that a key strategist from the opposition Liberal Party (which had originated the Pacific solution) “told us the issue was ‘fantastic’ and ‘the more boats that come the better’” (“Australia Searches,” 2009). Nonetheless, the argument that harsh measures were required to ensure that lives were saved in the seas to the northwest of Australia acquired a certain traction, even though the effect of a “successful” policy could actually be to drive asylum seekers into even more perilous routes of egress from danger.

What is important to understand here is the logic of deterrence. A policy of deterrence is unlikely to work unless the targets of deterrence have reason to fear that that they will suffer harm. The word “harsh,” used by former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull to describe his own party’s policy towards asylum seekers, captured this logic (Ireland, 2014). It dictates that the rights (and in the Khazaei case, urgent medical needs) of asylum seekers warehoused offshore be broadly subordinated to the wider objective of preventing asylum seekers from accessing Australian territory. The paradox, therefore, is that the system’s failure as far as Mr. Khazaei was concerned was a consequence in part of its working to advance the government’s policy settings. The disaster that befell Mr. Khazaei was a disaster waiting to happen.

Sometimes systems of this kind can be subverted by bureaucrats. It is clear, simply from the multiple layers of bureaucracy within the Department of Immigration and Border Protection through which a request for medical transfer had to be moved in order to access an approval, that the system was not a flexible one, and indeed the coroner captured this in a number of specific recommendations. In certain circumstances, officials have found ways of overcoming the constraints of such complexity. Indeed, some formal organizations develop an organic rather than a mechanistic culture in which flexibility becomes almost a standard operating procedure, and individual officials may display a flair for working around rules in an imaginative way (Burns and Stalker, 1994) (Shepsle, 2017). Unfortunately for Hamid Khazaei, there was little evidence of this in the Department of Immigration and Border Protection as steps to evacuate him from Manus Island stalled. Instead, a longstanding and well-documented “culture of control” prevailed (Cronin, 1993). The consequences proved devastating.

It is a considerable irony that in many countries, state policies that compromise the human rights of those seeking protection from persecution are being promoted or defended in the name of “border control” by political actors who in virtually all other circumstances express great skepticism about the uses to which state power might be put. A damaging consequence is that a great deal of power is being devolved to relatively low-level state officials whose decisions can have catastrophic effects on the liberties and even the lives of those in their charge. Enhanced mechanisms of accountability are necessary to address this problem, but building such mechanisms is no easy task (Mulgan, 2003). In the interim, therefore, it is more important than ever that one not lose sight of those vulnerable to state power. Refugees and asylum seekers are amongst the most vulnerable people one could wish to find (Clark, 2013).

V. Conclusion

In his Essay on Man, Alexander Pope famously wrote “Whate’er is best administer’d is best” (Ward, 1907). This begs the question for whom, and in what ways. For some ordinary people, this may not matter much. As Richard Rose has put it, “If we did a content analysis of what ordinary people talk about, we would find that talk about the weather, meals or sport was more frequent than talk about politics, and that phatic communication was more common than reasoned analysis of society’s ills” (Rose, 1989). But for ordinary individuals such as Hamid Khazaei, exposed to largely-untrammeled bureaucratic discretion, how a system is administered may matter very much indeed. In his case, it was administered not with his human rights as paramount consideration, but as part of an attempt to realize a range of objectives, some entirely unrelated to his rights. And his sad case may not be an isolated one, as the deaths in December 2018 of two Guatemalan children in the custody of US authorities, Jakelin Caal and Felipe Gómez Alonzo, make clear (Brice-Saddler, 2018; Jordan, 2018). One might hope that cases such as these would have a transformative effect on policy settings, and it is almost certainly the case that some of the individuals involved in the processes to which Hamid Khazaei fell victim are likely to carry a heavy burden of guilt about what happened. There is, however, one further and very sobering lesson from literature on disasters, and that is that the ability to learn from past failure should not be over-estimated. The forms of organizational dysfunctionality that contributed to the Columbia disaster were very similar to those which had contributed to the Challenger disaster and which had been identified by the Rogers Commission (Vaughan, 2005). This suggests that those who are concerned to protect human rights in an environment shaped by complex public policy calculations, where a range of factors can militate against effective organizational learning, will need to be extremely vigilant.

One final development makes this painfully clear. In August 2018, Scott Morrison, Minister for Immigration and Border Protection at the time of Hamid Khazaei’s death, managed to secure the position of Prime Minister, but by early 2019, and with an election looming, his government’s standing in the polls was dire, and as a result of resignations and defections, the government was no longer in a position to command a majority on its own in either chamber of the Australian parliament. The continuing resistance by the government to medical evacuations to Australia from Manus Island or Nauru had led to an increasing number of applications to the Federal Court of Australia to force the government to act. A scathing judgment in September 2018 by Justice Mortimer suggested that the bureaucratic problems that the coroner identified in the Khazaei case remained firmly in place: “There is no longer any excuse for the respondents, in particular at departmental and agency level, not having systems in place to respond quickly, effectively and appropriately to these applications, and to ensure that their legal representatives appearing in Court can secure the instructions they require” (ELF18 v. Minister, 2018). Faced with this continuing resistance, non-government members succeeded in forcing through the Parliament amendments to what became the Home Affairs Legislation Amendment (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2019, providing for the insertion in the Migration Act 1958 of a new section 198E to give the power to treating doctors to trigger a process that could force the ”transfer to Australia” of a person “not receiving appropriate medical or psychiatric assessment or treatment in the regional processing country.”

The response of Prime Minister Morrison was to announce the reopening of the mothballed immigration detention centre on Christmas Island, technically part of Australia but some 2,105 miles from the Australian mainland and notable for its lack of sophisticated medical services. The reported cost of reopening the centre was A$1.4 billion over four years (Koziol, 2019).

+ Author biography

Professor William Maley is Professor of Diplomacy at the Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy, where he served as Foundation Director from 1 July 2003 to 31 December 2014. He taught for many years in the School of Politics, University College, University of New South Wales, Australian Defence Force Academy, and has served as a Visiting Professor at the Russian Diplomatic Academy, a Visiting Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Public Policy at the University of Strathclyde, and a Visiting Research Fellow in the Refugee Studies Programme at Oxford University. He is a Barrister of the High Court of Australia,Vice-President of the Refugee Council of Australia, and a member of the Australian Committee of the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP). He is also a member of the International Advisory Board of the Liechtenstein Institute on Self-Determination at Princeton University. In 2002, he was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia (AM). In 2009, he was elected a Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia (FASSA).

+ Footnotes

Inquest into the death of Hamid Khazaei (Brisbane: Coroners Court of Queensland, 2014/3292, 30 July 2018) para.284. Subsequent references to paragraphs from this report appear in the text.

Quoted in Spencer S. Hsu and Susan B. Glasser, “FEMA Director Singled Out by Response Critics,” The Washington Post, September 6, 2005.

For a detailed discussion of this case, see Thomas Preston, “Weathering the politics of responsibility and blame: The Bush Administration and its response to Hurricane Katrina,” in Arjen Boin, Allan McConnell and Paul ‘T Hart (eds), Governing After Crisis: The Politics of Investigation, Accountability and Learning (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008) pp.33-61.

See Barry A. Turner, “The Organizational and Interorganizational Development of Disasters,” Administrative Sciences Quarterly, vol.21, no.3, September 1976, pp.378-397; Barry A. Turner, ‘The Development of Disasters—A Sequence Model for the Analysis of the Origins of Disasters’, Sociological Review, vol.24, no.4, November 1976, pp.754-774.

For further discussion, see William Maley, “Australia’s Refugee Policy: Domestic Politics and Diplomatic Consequences,” Australian Journal of International Affairs, vol.70, no.6, December 2016, pp.670-680.

+ References

“Australia Searches for Asylum Seeker Solution,” Cable Reference ID 09CANBERRA1006, U.S. Embassy, Canberra, 13 November 2009.

Brice-Saddler, Michael, “The 7-year-old girl who died in Border Patrol custody was healthy before she arrived, father says,” The Washington Post, December 15, 2018.

Burns, Tom and G.M. Stalker, The Management of Innovation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Clark, Ian, The Vulnerable in International Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013) pp.84-105.

Cronin, Kathryn, “A culture of control: an overview of immigration policy-making,” in James Jupp and Marie Kabala (eds), The Politics of Australian Immigration (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1993) pp.83-104.

ELF18 v. Minister for Home Affairs [2018] FCA 1368 (3 September 2018) per Mortimer J., para.18.

Etkin, David. Disaster Theory: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Concepts and Causes (Oxford: Elsevier, 2016) p.7.

Every, Danielle, “A Reasonable, Practical and Moderate Humanitarianism: The Co-option of Humanitarianism in the Australian Asylum-Seeker Debates,” Journal of Refugee Studies, vol.21, no.2, June 2008, pp.210-229.

Feynman, Richard P. The Pleasure of Finding Things Out (London: Penguin Books, 2001) p.169.

Hsu, Spencer S. and Susan B. Glasser, “FEMA Director Singled Out by Response Critics,” The Washington Post, September 6, 2005.

Inquest into the death of Hamid Khazaei (Brisbane: Coroners Court of Queensland, 2014/3292, 30 July 2018).

Ireland, Judith, “Malcolm Turnbull defends ‘harsh’ boats policy as necessary,” The Sydney Morning Herald, May 7, 2014.

Jervis, Robert, System Effects: Complexity in Political and Social Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997) p.6.

Jordan, Miriam, “A Breaking Point: Second Child’s Death Prompts New Procedures for Border Agency,” The New York Times, December 26, 2018.

Koziol, Michael. “A decade in detention: refugees face indefinite time on Christmas Island,” The Sydney Morning Herald, March 10, 2019.

Maley, William, “Australia’s Refugee Policy: Domestic Politics and Diplomatic Consequences,” Australian Journal of International Affairs, vol.70, no.6, December 2016, pp.670-680.

Maley, William, What is a Refugee? (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016) p.11.

Mulgan, Richard, Holding Power to Account: Accountability in Modern Democracies (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

Namah v. Pato. 2016. PGSC 13 (26 April 2016).

Preston, Thomas. “Weathering the politics of responsibility and blame: The Bush Administration and its response to Hurricane Katrina,” in Arjen Boin, Allan McConnell and Paul ‘T Hart (eds), Governing After Crisis: The Politics of Investigation, Accountability and Learning (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008) pp.33-61.

Rose, Richard, Ordinary People in Public Policy: A Behavioural Analysis (London: Sage Publications, 1989) p.178.

Roseman, Mark. The Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution: A Reconsideration (London: Folio Society, 2012); Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986) pp.617-651.

Sartori, Giovanni. “Concept Misformation in Comparative Politics,” American Political Science Review, vol.64, no.4, December 1970, pp.1033‐1053 at p.1035.

Shepsle, Kenneth A., Rule Breaking and Political Imagination (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention (Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission, 2014).

Turner, Barry A., “The Organizational and Interorganizational Development of Disasters,” Administrative Sciences Quarterly, vol.21, no.3, September 1976, pp.378-397

Turner, Barry A. ‘The Development of Disasters—A Sequence Model for the Analysis of the Origins of Disasters’, Sociological Review, vol.24, no.4, November 1976, pp.754-774.

Vaughan, Diane, “System Effects: On Slippery Slopes, Repeating Negative Patterns, and Learning from Mistake?,” in William H. Starbuck and Moshe Farjoun (eds), Organization at the Limit: Lessons from the Columbia Disaster (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2005) pp.41-59.

Ward, Adolphus William (ed.), The Poetical Works of Alexander Pope (London: Macmillan & Co., 1907) p.215.