While the exact effects of TNCs remain unknown, it is clear that taxi companies in many major cities have been under increasing stress in recent years. In New York City, taxi medallion prices had increased quickly over the course of the 2000s, peaking in June 2013. However, they have now fallen 28% from that peak (Barro 2015). The NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission estimates that drivers in 2012 earned an average of $130 a day, down from $150 in 2006—a reduction of almost 25% when adjusted for inflation (Grynbaum 2012). And since 2012, the number of taxi trips in New York City has decreased by 8% (Wallsten 2015). Taxis have seen declining revenues in other cities well. In Seattle, the addition of as many as 5,000 TNC drivers since 2013 resulted in a 28% decrease in taxi company revenues (Soper 2015). Taxi markets in Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia have seen similar trends (Madhani 2015).

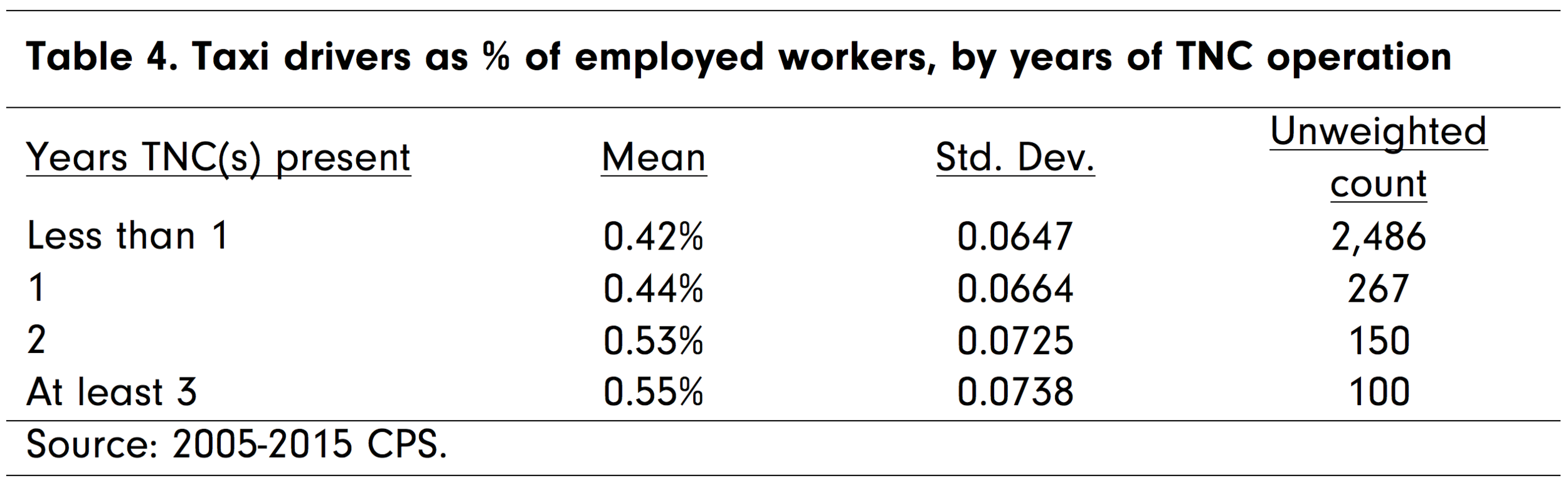

However, it remains unclear how overall taxi driver employment has been affected by the rise of TNCs. As of October 2015, there were 52,612 medallion drivers licensed to drive yellow cabs in New York City, down 2.2 percent from the end of 2014 (Fischer-Baum and Bialik 2015), although analysis of CPS data shows that nationally, the proportion of taxi drivers and chauffeurs in the workforce returned to its 2010 levels by 2015 (Figure 1).

Independent contractors and the sharing economy

Independent contracting and alternative work arrangements are far from new; research over the past 20-30 years has looked at the rise of the use of contracting by firms and the characteristics of workers who are employed as regular employees compared with those who are retained as independent contractors (Davis-Blake and Uzzi 1993, Bidwell and Briscoe 2009).

One way to examine the changing labor landscape is through the rise of “contingent workers.” Reviews of the data landscape by Annette Bernhardt (2014) and the U.S. Government Accountability Office (2015) have already identified the main sources of data available, the definitions of contingent work commonly used in academic and policy discussions, and the main gaps in data and research around this topic. The best source of data has previously been the Contingent Worker Survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, but the agency has not had funding to conduct the survey since 2005.

These nonstandard work arrangements are of interest to policymakers for many reasons, not least because contingent workers are two-thirds less likely than traditional workers to have workplace retirement plans, and less than half as likely to have health insurance through their employer (GAO 2015). Recently, the rising visibility of the gig economy has also increased policymakers' interest in non-standard forms of work in general, and in the effect of Uber on labor markets in particular. Quality data about workers in non-standard arrangements have been limited in recent years, however, as have detailed data about sharing economy participants.

Depending on how it is defined, the contingent workforce alternately estimated to be as little as less than five percent of the employed labor workforce or as much as a third.[vii] Using GSS data from 2010, the GAO identified a “core” group of contingent workers, defined as workers who lack job security and whose work schedules are variable, unpredictable, or both (such as agency temps, direct-hire temps, on-call workers, and day laborers). The agency estimated that this core group of contingent workers constitutes about 7.9 percent of the 2010 labor force, and similar proportions in 2005 and 2006. In late 2015, Katz and Krueger attempted to replicate the BLS surveys from 2005 and before using the RAND American Life Panel. Their findings suggest that the share of workers in alternative work arrangements has risen from 10.1% in early 2005 to 15.8% in late 2015, with online gig platforms (such as Uber) accounting for only a small part of this growth—about 0.5 percent of all workers in 2015 (Katz and Krueger 2016). However, they note that more research is needed to understand the causes of this increase.

Measuring the size of the sharing economy workforce in particular has been a challenge for researchers, due to the aforementioned hurdles in data collection combined with the newness of the industry. Measures of non-standard work in government surveys often does not match administrative or tax data (Abraham et al 2013), and standard survey questions do not appear to capture the nuances of work arrangements that the gig economy facilitates, such as the prevalence of multiple “gigs” in addition to a full-time traditional job. Even administrative data can be of limited use due to the workers’ official “independent” (i.e. non-payroll) status.

In 2015, Harris and Krueger estimated that “about 600,000 workers, or 0.4 percent of total U.S. employment, work with an online intermediary in the gig economy” as of late 2015, based on projecting recent Uber workforce growth rates and indexing these rates with the relative prevalence of web searches for other gig economy platforms (Harris and Krueger 2015). Researchers at the JPMorgan Chase & Co. Institute reached similar conclusions: After analyzing transactions from a random sample of one million primary account holders from October 2012 to September 2015, they found that in any given month, 0.4 percent of bank account holders received earnings from labor platforms such as Uber and Taskrabbit (Farrell and Greig 2016).

Similarly, there has yet to be a deep analysis of the effect these new types of companies have in the cities they operate in. One paper used a differences-in-differences approach to look at the effect of Airbnb on hotel revenue in Texas, for instance (Zervas 2015), while a recent Harvard Business Review article uses Census data about non-employee firms to compare the effect of sharing economy “gigs” in San Francisco in 2009 and 2013, an approach with its own set of limitations (Hathaway 2015).

How this paper contributes to the literature

Nationally, the total number of drivers for Uber and Lyft collectively equal the size of the entire taxi industry (Cramer and Krueger 2015), and some data show that these new drivers are directly competing with taxi drivers for business. But most analyses of the impact of TNCs on the taxi industry have looked at indicators only in New York City—which, while a major metropolitan center and a vital piece of the taxi industry, is unique in many characteristics. These include its size and density (NYC 2015), use of public transportation (Anderson 2016), and the long history of the taxi industry there (Hodges 2009), making it difficult to expand those trends to the entire country (Cramer and Krueger 2015). As far as I am aware, there has not yet been an analysis of the impact of TNCs on national taxi driver employment that takes into account broader trends such as the changing demographics of the industry or the specific pattern of TNC expansion.

Uber has also had an impact outside the taxi industry by pioneering new logistics systems that allow coordination of large flexible workforces, and the collective impact of these online platforms is still largely unexplored. While there have been many analyses that attempt to discern the sharing economy’s impact on the U.S. workforce using descriptive statistics, most have not accounted for larger demographic and economic trends. Few have looked specifically at metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) where TNCs are active (Hall and Krueger 2015), and none, to my knowledge, have controlled for TNCs’ presence in a national context. This is important because the recent nature of Uber’s rise and relatively small size of its workforce, and the fact that it has spread to different cities at different times, means that broad analyses may not detect present changes due specifically to these companies.

This paper contributes to the literature by examining the effect of TNCs on the taxi labor market. It is a first attempt to control for the specific patterns of TNCs’ expansion in a way that has not yet been done.

III. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

TNC impact on taxi driver employment

Uber officially launched in San Francisco in 2010, but it wasn’t until 2012 that UberX, Lyft, and Sidecar were launched and TNCs began to directly compete with taxis on a large scale. The rise of TNCs happened as the national economy was slowly recovering from the Great Recession, meaning many workers were still looking for opportunities to work part-time to augment their regular income or tide them over between full-time jobs. Another factor at the time was the “bursting” of the taxi medallion bubble in New York City and the general dip in taxi employment after the recession, which began to recover by 2014-2015 even as revenues in major cities often declined.